A practical guide to LTTng buffer allocation strategies

When configuring LTTng for tracing, one of the most important decisions is how to allocate and manage channel buffers. These buffers are at the heart of the tracer: they temporarily hold trace data before LTTng writes to disk or sends over the network. How you configure them determines the tradeoffs you make between performance, memory usage, and process isolation.

LTTng 2.15 brings new buffer parameters and features that make channel buffer configuration even more flexible, giving you finer control over how the tracer manages memory.

This all happens at channel creation time using the

lttng enable-channel command.

This post explains the different buffer allocation options, their tradeoffs, and when to use each one.

If you're in a hurry, you can skip to the summary table or final thoughts.

What's a ring buffer?

The channel buffers mentioned above are in fact ring buffers: fixed-size, circular data structures that LTTng uses to store trace data in memory. When the tracer records an event, it writes the resulting event record to one or more ring buffers. A consumer daemon periodically reads from the buffers and writes the data to trace files or sends it over the network.

The "ring" part is key: when the buffer fills up and wraps around, what happens to old data depends on your configuration (more on that later).

What's a sub-buffer?

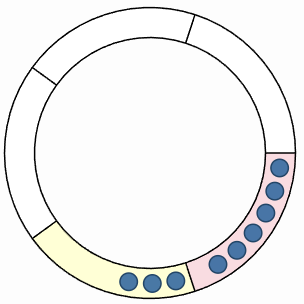

Each ring buffer is divided into multiple sub-buffers. Think of them as equal-sized slices of the ring buffer that can be independently managed.

A ring buffer with five sub-buffers, some containing event records.

Here's how they work:

-

The tracer writes event records to the current sub-buffer.

-

When a sub-buffer fills up, the tracer marks it as consumable and switches to the next available one.

-

The consumer daemon reads consumable sub-buffers and writes them to disk.

-

Once consumed, a sub-buffer becomes available again for new events.

The sub-buffer is the unit of:

- Consumption

- The consumer reads whole sub-buffers, not individual event records.

- Loss

- In overwrite mode, you lose a whole sub-buffer at a time (more on this below).

- Memory reclaim

- LTTng reclaims memory at sub-buffer granularity.

Getting the balance right between sub-buffer size and count affects both memory usage and the risk of losing trace data; see Extra: tune sub-buffer size and count below.

The big picture: three dimensions of buffer configuration

LTTng user space tracing offers three independent configuration "dimensions":

- Buffer ownership model

-

Who owns the buffers?

Think memory vs. process isolation.

- Buffer allocation policy

-

One ring buffer per CPU or per channel?

Think throughput vs. memory.

- Buffer preallocation policy

-

Allocate memory upfront or as needed?

Think predictability vs. initial footprint.

Additionally, you can control memory reclaim operations to free unused buffer memory over time.

Let's look at each one.

Buffer ownership model

This determines the isolation boundary for ring buffers. Essentially: who shares buffers with whom.

Read this section if you're tracing multiple processes and need to decide between memory efficiency and process isolation.

The --buffer-ownership

option controls this parameter.

| Model | Pros | Cons | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Per user. All instrumented processes of a given Unix user share the same set of ring buffers.

Use the |

|

|

Development environments, single-application systems, or when memory is tight. |

|

Per process. Each instrumented process gets its own set of ring buffers.

Use the |

|

|

Production environments, multi-tenant systems, or when process isolation is critical. |

|

System. A single set of buffers for the entire system.

This is only for Linux kernel tracing, therefore you don't

need to specify the |

|

|

Linux kernel tracing. |

Buffer allocation policy

Available since LTTng 2.14, this determines how buffers map to CPUs.

Read this section if you're tracing a multi-core system and need to balance tracing throughput against memory usage.

The --buffer-allocation

option controls this parameter.

| Policy | Pros | Cons | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Per CPU. One ring buffer per CPU. This is the default.

Use the |

|

|

High-throughput tracing, production systems, or multi-core machines. |

|

Per channel. A single ring buffer shared across all CPUs.

Use the This is only available for user space tracing. |

|

|

Low-throughput tracing, memory-constrained environments, or single-CPU systems. |

Buffer preallocation policy

Available since LTTng 2.15, this determines when backing memory is allocated.

Read this section if you care about predictable performance vs. minimizing initial memory footprint.

The --buffer-preallocation

option controls this parameter.

| Policy | Pros | Cons | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Preallocate. Allocate all buffer memory when LTTng creates the channel. This is the default.

Use the |

|

|

Production systems where predictability matters, real-time applications, or systems with known memory budgets. |

|

On demand. Allocate buffer memory incrementally, as sub-buffers are needed.

Use the This is only available for user space tracing. |

|

|

Development environments, systems with sporadic tracing, or memory-constrained systems where initial footprint matters. |

Memory reclaim

So far we've talked about allocating memory. But what about giving it back?

LTTng can reclaim memory from consumed sub-buffers, effectively shrinking buffer memory usage during periods of low activity.

A memory reclaim operation for memory older than 40 seconds.

This feature is only available for user space tracing, and since LTTng 2.15.

How it works

When the LTTng consumer daemon consumes a sub-buffer, its backing memory can potentially be released back to the system. The reclaim operation checks:

- In discard mode

- Only reclaims sub-buffers that have been both delivered and consumed.

- In overwrite mode

- Can reclaim any delivered sub-buffer (the tracers will overwrite old data anyway).

You can specify an age threshold: only sub-buffers closed more than some time ago are eligible.

| Operation | Description |

|---|---|

|

Automatic reclaim.

See the

|

Let LTTng handle it automatically. LTTng periodically checks sub-buffer ages and reclaims those older than the threshold. $

lttng enable-channel --userspace my-channel \

--auto-reclaim-memory-older-than=10s

Best for: long-running sessions with variable event throughput, or systems where memory should be released during idle periods. |

|

On-demand reclaim.

See the

|

Manually trigger memory reclamation when you know activity has dropped. $ lttng reclaim-memory --userspace my-channel $ lttng reclaim-memory --userspace --older-than=5s my-channel |

Quick note on event record loss

When all sub-buffers are full and there's no room for new events, something has to give.

The

--discard and

--overwrite

options control what happens:

- Discard mode (default)

- Drop new events until a sub-buffer becomes available. LTTng counts how many events were lost and writes this count to the trace.

- Overwrite mode

- Overwrite the oldest sub-buffer. You keep recent data, but lose older data.

This interacts with memory reclaim operations: automatic reclaim only works in discard mode, since in overwrite mode you might reclaim a buffer that's about to be reused.

Putting it together: common configurations

Here are a few reasonable channel buffer configuration examples.

High-performance production tracing:

$

lttng enable-channel --userspace my-channel \

--buffer-ownership=process \

--buffer-allocation=per-cpu \

--buffer-preallocation=preallocate \

--subbuf-size=16M --num-subbuf=4

You get process isolation, no CPU contention, and predictable memory. You pay upfront for consistency.

Memory-constrained development

$

lttng enable-channel --userspace my-channel \

--buffer-ownership=user \

--buffer-allocation=per-channel \

--buffer-preallocation=on-demand \

--auto-reclaim-memory-older-than=30s

You get minimal footprint and memory released when "idle". Good for laptops or containers with tight limits.

Balanced production setup

$

lttng enable-channel --userspace my-channel \

--buffer-ownership=user \

--buffer-allocation=per-cpu \

--buffer-preallocation=on-demand \

--auto-reclaim-memory-older-than=1m

You get good throughput with adaptive memory usage. A reasonable middle ground.

Summary table

| Option | Memory impact | Performance impact | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

--buffer-ownership=user |

Lower | Risk of cross-process interference | Dev, single app |

--buffer-ownership=process |

Higher | Complete isolation | Production, multi-tenant |

--buffer-allocation=per-cpu |

Higher | Better scalability | High throughput |

--buffer-allocation=per-channel |

Lower | Contention possible | Low throughput |

--buffer-preallocation=preallocate |

Higher upfront | Consistent | Production, real-time |

--buffer-preallocation=on-demand |

Lower initial | Slight overhead during growth | Dev, sporadic tracing |

--auto-reclaim-memory-older-than |

Adaptive | Minimal | Long-running, variable load |

Extra: tune sub-buffer size and count

You control sub-buffer configuration with two parameters:

| Parameter | When to use less | When to use more |

|---|---|---|

|

Sub-buffer size. Size of each sub-buffer.

Use the

|

|

|

|

Sub-buffer count. Number of sub-buffers per ring buffer.

Use the

|

|

|

The total ring buffer size is simply one times the other.

Final thoughts

There's no single "best" configuration: it depends on your constraints.

If you're unsure where to start:

-

Start with defaults and measure actual memory usage and event record loss.

-

Increase sub-buffer size if you're losing event records.

-

Switch to per-process ownership if you need isolation between applications.

-

Consider per-channel allocation if you're on a single-CPU system or tracing throughput is low.

-

Enable on-demand preallocation + automatic memory reclaim if memory is tight and tracing is sporadic.

The flexibility is there so you can tune LTTng to your specific situation.

As always, happy tracing!